Why Death Changes Everything

A woman died because of a cyberattack in Dusseldorf, and the world is different because of it.

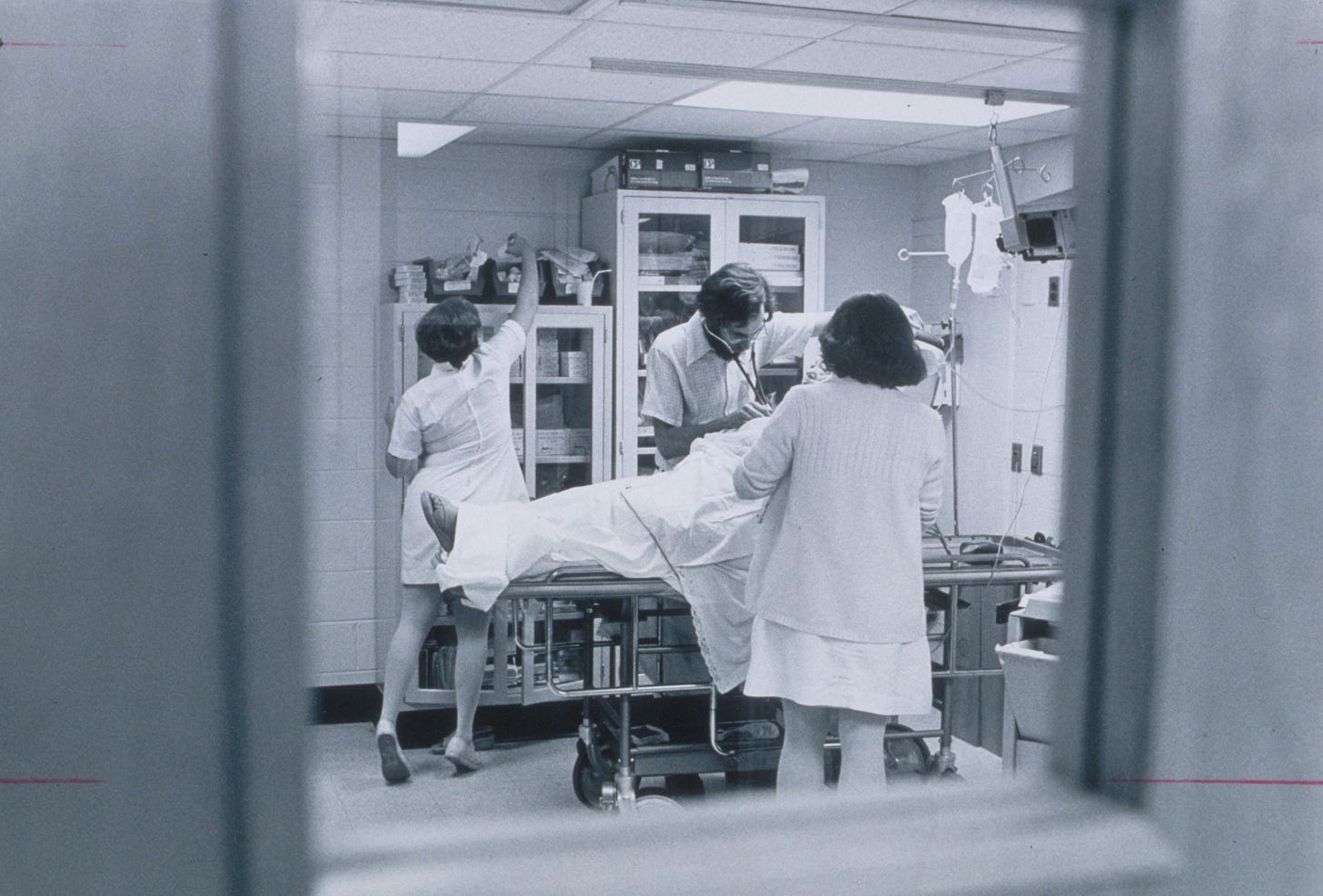

"West Hospital Emergency Room" by VCU Libraries is licensed under CC BY 2.0

BLUF: When death is on the line, individuals cannot act rationally, reducing strategic options.

Last week cybersecurity crossed a major threshold: a cyberattack killed someone, for real. If you do not regularly read the OSIRIS Brief, you might have missed it, because in the bustle of international politics, one woman’s death for any reason may not seem news worthy. Nonetheless, it is plausible that (out of all that happened in 2020) the passing of a single woman in a medium sized German city may be the most important event this year. This death represents a fundamental change in cyberpower, because death changes everything.

Up until last week, however costly cyberattacks were, they always stopped short of killing someone. At first, cyberattacks could only create effects in the online world. Stuxnet was the first time a cyberattack created real-world damage by causing Iranian centrifuges to malfunction. The Dusseldorf ransomware attack killing someone is like attaching a Hellfire missile to a Predator drone. What had been information, became fatal.

Killing someone with a cyberattack transforms cyberstrategy by making cyberattacks more like warfare. War is the ne plus ultra of competition, and war involves killing. If cyberattacks cannot kill, many of the logics of war will inherently not apply, and there is some level of competition beyond cyberattacks to which actors can resort. Once war has begun, however, for each participant it is possible to lose absolutely everything. The possibility of “the ultimate sacrifice” prevents some of the rationalization possible with other competition.

We Should Not Be Rational About Our Own Deaths

Rationality, in the strictest sense—and how I use it in this essay—means “expressible as a ratio.” You are being rational when you weigh and consider the relative value of different options that are not inherently equal. To be able to rationalize between two unequal values, both must be subdivisible or multipliable. I can say that a candy bar is worth $0.75, $1 gets you 1 1/3 candy bars, or $3 buys 4 candy bars, because I can divide and multiply both dollars and candy-bars.

You cannot, nor should you be, rational about your own life or the lives of those you care about. Miracle Max notwithstanding, there is no such thing as “mostly dead.” You cannot subdivide your life, and you only get one (make the most of it). It is not possible to trade 1/100th of your life for more security.

When your life is threatened, you should not—and indeed cannot—be rational about it. Irrationally valuing your life is not succumbing to primal passions. As Clint Eastwood observed, “It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. You take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have.”

With rounds inbound, you should not think about the improbability of those bullets hitting you, or the unlikelihood of you dying even if shot (which are true). You rightly consider the loss of your everything, and act accordingly. It takes years of training and intestinal fortitude stand and fight in the face of potential death. Even still, good soldiers don’t turn tail because they are more rational about their own death, but because training teaches them survival is more likely by taking and returning fire.

Unfortunately, in common parlance we use “rational” to mean “smart,” “reasonable,” or “justifiable,” which distorts the meaning. Most preferences are irrational, and indeed it would be strange if they were not. People don’t prefer chocolate ice cream to vanilla because chocolate provides 1/3rd more mental stimulation than vanilla, and parents don’t love their children because a child is worth 500 candy-bars. We would think someone is a psychopath if they thought that way.

Rational Irrationality Makes Strategy Work

The fear of death, either our own or that of a loved one, is the ultimate policy backstop. Fear of death cannot be bought off, bargained with or reasoned away; it can only be accounted for. Death the bedrock upon which all military strategy rests, and without it, strategy collapses like a foundationless building.

Military strategy works because leaders are rational about the limits soldiers’ fear of death imposes on their own and their opponents options. Strategy’s intent is not to “mak[e] the other poor dumb bastard die for his country.” Military strategists threaten opponents’ lives hoping cause their opponents to retreat or surrender. Death often results, but a military victory without fatalities remains a victory nonetheless. Military strategies totally annihilating one military force are so rare they assumemythic or heroic qualities.

Military leaders can be rational about the lives of those below them in a way those subordinates cannot be rational about their own lives. While losing your life is an incalculable loss to you, losing soldiers lives is calculable to an army or a state, however terrible the cost. However, soldiers attachment to their own lives forecloses certain options for leaders. Even if leaders correctly believe that a strategy likely to kill 10% of the soldiers under their command would end the war in they favor today, most leaders and subordinates would be loathe to pursue such a strategy unless all other options were worse.

The possibility of death also makes some international policies more effective than others. Painful but survivable policies, like sanctions, rarely work, in large part because the costs can be subdivided and shared out. Violence is not a perfect tool, either, but as mortality rises, it becomes more difficult to resist coercion. Once militaries can provide no protection whatsoever,governments concede.

The possibility of death also makes primary deterrence robust, preventing leaders from backing down if attacked. No one should (and no serious person does) doubt that any government would retaliate against attacks that kill people. While the government can (and should) weight the costs rationally, people losing their everything and the fear it provokes among their fellow country-people, is beyond normal human ability to rationalize. As Thomas Schelling pointed out, the USSR never doubted the US would retaliate if the Soviets bombed New York, or even Sault Ste. Marie. The challenge was convincing them the US would trade New York for Frankfurt. India and China’s behaviors on their shared border are responding to the deaths of several dozen soldiers.

Death in Cyberspace Makes Cybersecurity Easier

Because cyberattacks have never before drawn blood, military logics did not apply, frustrating many strategists. While other problems also intervene, such as difficulty in attributing cyberattacks, attacking with and defending against cyberattacks using existing military logics fails because the basic assumption of military logic does not hold. Without the backstop of death and the natural human aversion to it, there is no constraint on “rationalization” by both attacker and defender.

Cyberattacks’ purely pecuniary penalties allow attackers and defenders to reduce all attacks to manageable sub-components. Smart attackers can infinitely subdivide targets, inflicting infinite small costs each of which the defender can address atomically, as discrete events. Defenders, for their part, can—and usually do—rationalize the costs, reasoning correctly that whatever fiscal impact an attack imposes, the cost of retaliation or escalation will increase costs with little gain. Coercion founders because there is no immovable wall to press an adversary against. Deterrence fails because there is no credible foundation to consistently launch a counter-attack from.

Online strategy fell to other tools, with more solid foundations, until last week. It is no longer possible to say, “We lost a trillion dollars, but at least no one died,” except in relief at one’s good fortune. From this point forward, we have definitive evidence could kill someone. While “yet another way to die in 2020” hardly seems like good news, we should take heart that some heretofore ineffective strategies may work, increasing overall security.

Cyberdefense is no longer a matter of mere financial risk, becoming meaningfully mandatory. When all costs are financial, leaders and planners could reasonably rationalize marginal expected costs and marginal expected benefits, sometimes concluding it would be better to risk the cost than pay for prevention. The possibility of death puts a backstop to such rationalization. While leaders can rationalize about “lives” generally under their care, there is a compressed window for such rationalization. Individual fear of the “infinite cost” disallows subdivision of problems, and forces decision-makers to treat cybersecurity as a problem with potential tremendous costs.

Cyberdeterrence becomes easier because retaliation is easier to signal, at least under certain circumstances. The attackers in Dusseldorf did not seem to intentionally target a hospital, and cyberattacks hitting unintended targets have a long history. It is now more plausible that a government would retaliate against certain kinds of cyberattacks, even if no one died, because we know for sure someone could have. Not all retaliation is equally credible, but attacks now know that defenders cannot back up forever when attacked, and may hit the point where irrational retaliation becomes more plausible.

We’re Not in a Brave New World Just Yet

Although a cyberdeath is a watershed event in history, and is likely to be remembered as such, international relations rarely turns on such dimes. An apparently accidental fatality is not the same as a demonstrated, replicable ability. Furthermore, killing people who are (or should be) in hospitals is particularly sinister as they are the most vulnerable and merit the most moral protection, but is also the least strategically significant. People die in hospitals all the time, and a slight increase in the hospital fatality rate is politically less consequential than killing people who were not already at risk otherwise.

While the Dusseldorf ransomware attack is not the “Trinity Test,” it is a definitive demonstration of a capability speculated on, but never before proven. It is one thing to believe something is possible in theory. It is another thing altogether to point to a historical case proving the theory. If nothing else, a real event is persuasive to everyone in ways theories—with potentially hidden assumptions and misunderstood mechanisms—may not be.1

The Dusseldorf ransomware attack also points to potential mechanisms to kill people that I have not seen explored in detail elsewhere. Most speculation surrounding how to use a cyberattack to kill people in hospitals focused on digital equipment. We forget, and the Dusseldorf attack puts in stark relief, how important computers are for cumulative health care efficiencies that are not themselves intrinsically vital. I doubt most people would have imagined that the inability to in-process someone at a hospital might would kill them, but we now have empirical proof that it can.

We can see in our immediate environment how facts learned from the Dusseldorf attack might affect politics right now. APTs have attempt to hack research on COVID-19. Now, with a defined example of death from indirect interference in medical processes, retaliation and escalation over such attacks is more credible. Governments should immediately explore the types of attacks which they must deter and the retaliatory attacks they can now credibly threaten, to deter potential interference in COVID-19 vaccine distribution.

David Benson is a Professor of Strategy and National Security focusing on cyberstrategy and international relations. You can reach him at dbenson@osiriscodex.com. If you are a government planner for the US or any US ally and want assistance with planning a deterrent strategy for COVID-19 contact me, and we can establish secure communications.